Veterinary

Information for students considering veterinary medicine

Veterinary medicine is a challenging and rewarding career path. Many of those who pursue this career acknowledge the huge satisfaction they derive from their work. Yes, it does bring above-average earnings and a certain amount of social prestige too - but the job is hard, both physically and emotionally. Most agree that the many highs make the job worth the lows, but it is important that students think carefully before committing to this career ambition. Students should be honest with themselves. Is this career their dream, or their parents'? Is their temperament and academic performance appropriate? Uncomfortably, and perhaps for the first time, students must look honestly at their personal attributes to see if they suit this demanding career path. This guide provides a short overview of some aspects worth considering before students commit:

Why do it?

Temperament and personal attributes

Veterinary is a demanding profession and, as a result, requires a demanding set of personal attributes. Admissions tutors will want to see evidence that students have a genuine interest and motivation for this career. Students must also be all-rounders: intelligent and highly sociable. Empathetic and level-headed. Sensitive, yet confident and assertive. Admissions tutors are usually uninterested in students ‘having always wanted to be a vet’ or having family members who have been vets unless they can articulate why this makes them a better candidate.

Aware of the demands… yet still interested

Prospective applicants must have an interest in, and an awareness of, the substantial demands of this job and of the professional standards and regulations vets work within. Indeed, this challenge can be what attracts prospective veterinary students to the profession. Working practices are also constantly changing - so students must be flexible thinkers, adaptable and open to change.

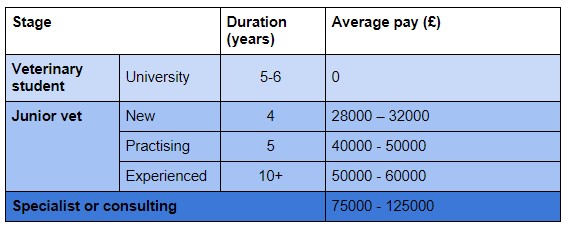

Earnings

Vets are well-paid professionals, earning significantly above national average salaries, particularly in the south-west of England. This pay only follows a significant amount of study and training, as outlined below:

Entry requirements

Veterinary is amongst the longest and most demanding of degree courses, ranging from 5-6 years. Veterinary schools therefore insist on some very strict entry requirements in order to short-list only the most talented applicants.

Applicants will need to demonstrate the following nine attributes for their application to be considered:

Most GCSEs graded 9-6*

Most veterinary schools require GCSEs to be graded between 9-6 as a minimum. This must include English language, mathematics and two science grades. A small minority of veterinary schools accept grades as low as 4, and others insist that they are between 9-8. The practical reality is that the vast majority of students applying will have GCSEs significantly higher than grades 9-6. Indeed, many will present applications where every GCSE is graded 9. So, to increase the chances of a successful application, most grades should really be between 9-7.

Studying A-level Chemistry and another science, preferably Biology*

To allow students to choose between all 40 veterinary schools, it is vital that they have A-levels in both Chemistry and Biology. If students do not study A-level Biology, half of all veterinary schools will not accept applications. It would be a mistake to study Chemistry and Biology purely to pursue a veterinary career if students do not enjoy them.

Studying a suitable third A-level*

This can more or less be any A-level. It should be a subject that is enjoyed by a student and where they have a high chance of getting an A* or A grade, whether it is Art, French or Geography. A common error is for students to select additional science-based A-levels that they would not ordinarily choose because they think this will enhance their application. Only two veterinary schools insist upon more than two sciences (Aberdeen and Glasgow). Of course, if students do not really like Chemistry or Biology, they should not take them at A-level nor should they pursue a veterinary career. The third A-level cannot overlap significantly with another subject being studied. For example, PE is not counted alongside Biology and Further Mathematics is not considered alongside Mathematics. Another misconception is that doing four A-levels adds value to an application - it does not. Admissions tutors advise that doing more than three A-levels should only be for the personal development of students and will not be considered as part of their application.

Routinely getting As in assessments in Year 12*

Students suited to veterinary are academically very strong and rarely struggle with assessments. They will know this by routinely getting A*s, As and Bs in their assessments.

Predicted A* or A by all of A-levels subjects at the end of Year 12 / early Year 13*

One thing students must appreciate is that their predicted grades will determine their university choices, and not the other way round! This may seem harsh, but it is the reality. Occasionally, students plead (unsuccessfully) for increases to their teacher’s judgement because they ‘need’ an A grade for one course or another. This is not how the process works. Students are provided with predictions, and it is those predictions which determine their university choices. If they are not predicted the grades for their initial course preference, then their university application must promptly be directed towards another subject. The school will not increase grades purely to suit an application. If veterinary remains a passion, despite a student’s academic ability not yet being high enough, there are always postgraduate routes into Veterinary after they have already started university. There are always options!

Achieves A*s or As in all of their A-levels*

This might seem obvious, but showing exceptional performance in Year 12 is only part of a student’s successful journey. They must also achieve the grades too, since offers made by veterinary schools will be conditional upon this. Very occasionally, if students are impressive at an interview, they might be lenient if they over-perform in one area to make up for underperformance elsewhere, i.e. allowing A*A*B instead of A*AA. This is a rare exception, rather than a rule.

There are veterinary schools that will adjust your offers based on a top grade in your extended project, so don’t ignore it.

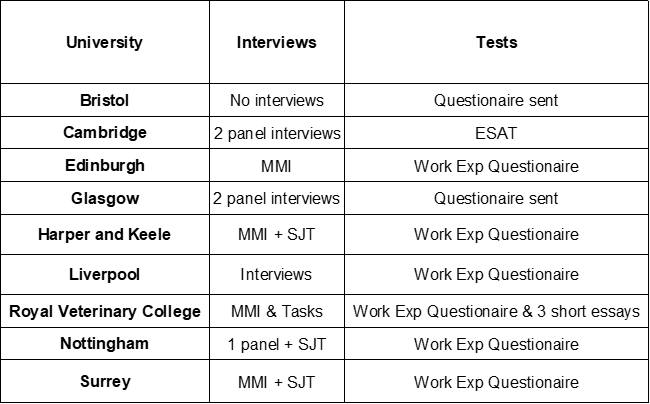

Admissions test

Veterinary UCAS applications must be supported by further evidence. For veterinary medicine, each university uses its own mix of questionnaires and situational judgement tests. Some of these tests are completed online, but after your UCAS application has been sent, these are then used to decide if you get an interview. There is a heavy weighting on the work experience forms. Cambridge University has students take the Engineering and Science Admissions Test in October of Year 13, before UCAS applications are submitted. The following table summarises the different tests.

Have a good knowledge of healthcare careers and the NHS

Students must have a good working knowledge of the NHS structure, as well as its core principles, values and pledges as defined in the NHS Constitution. They must be aware of the GMC and its role. Students must also be knowledgeable of the important skills and character traits that make for a successful veterinary professional. This knowledge must be evident in their 4000-character UCAS personal statement and will likely be assessed during interview.

A reasonable period of volunteering and/or work experience

Veterinary schools acknowledge that veterinary work experience can be difficult to obtain, and will be flexible. At the very least, students should have an awareness of the working environment of vets, such as GP surgeries, even if limited to a small number of visits. Volunteering, however, is easier to come by and will demonstrate that a student has some of the necessary personal attributes. Appropriate examples of volunteering should be regular and over a sustained period of time, such as a number of months or longer. The setting can be varied, such as charitable work, or in a care setting, like a nursing home or special school.

What are the odds of getting in?

Veterinary is the most competitive university choice. Even if students have all of the above features, on average, only half of those eligible to apply are called to interview. Only 13% of eligible applicants successfully gain a place with around 9 people applying per space. Therefore, it is crucial that they have a plan B!

Students can only apply to four veterinary schools on their university application, but they are allowed to apply to a fifth, non-veterinary course. This course tends to still be healthcare related. Courses such as pharmacy, pharmacology, biomedical sciences, biological sciences are usual examples. This fifth option can be used in one of three ways:

-

It can be a back-up choice in case students receive no offers from veterinary school applications.

-

It can be used as their insurance choice if they receive one or more veterinary school offers but are uncertain that they will get the required grades.

-

It can be ignored altogether if they get two or more veterinary offers and choose them as their firm and insurance choice and are confident they will get the grades for them.

Where should I apply?

Do your homework! There are 11 veterinary schools in the UK. Each veterinary school has slightly different entry requirements. Each veterinary school places slightly different emphases on GCSEs, A-level predictions, entrance examinations, work experience and other factors. So, ask yourself: which most matches your personal and academic circumstances? For example:

- 9 out of 11 veterinary schools insist upon both A-level Chemistry and A-level Biology.

- 2 out of 11 veterinary schools permit psychology as ‘a second science’ A-level.

- 9 out of 11 veterinary schools require A-level grades at AAA or higher. [Can change yearly]

- 4 out of 11 veterinary schools use an interview panel, while the rest use MMI. [Can change each year]

- Final meeting with Dr Doddrell to choose the best options.

The interview

There are two common interview types:

1. The multiple mini interview (MMI)

The MMI is far more common, with 33 of the 40 veterinary schools using it to select potential students. In this set-up, students will rotate around a series of up to 10 ‘stations’, where they spend a few minutes interacting with an interviewer about a particular topic. The exercises range from a role play where students console distressed patients to a data analysis exercise, a science question, an interview about their interests, a hand-eye coordination assessment, a discussion about recent changes in the NHS etc.

2. The panel interview

A much rarer interview style with only six veterinary schools using them to select. This is a traditional interview where students will speak with two to four individuals about their application, science knowledge, NHS knowledge, their interests in veterinary etc.

Note: Some universities have moved their interviews to an online platform and this could become 'the normal' to save on student's travel time. Some prefer the interviews to take place 'in person' as they like to judge personal interaction at the same time.

Summary Table of Entry Guidance

Please click on the link for the entry guidance for UK universities.